Nask

Nask

Nask

Beauty Is Not a Privilege: Rethinking Aesthetics as a Path to Freedom

A journey through codes, cultures, and gestures, toward an inclusive, emotional experience of beauty, and a lifelong mission for designers and art directors.

The beauty we explore here, in its visible forms through space, objects, and signs, is not a privilege. It is a language rooted in culture, expressed through codes that vary from one group to another. Aesthetic is how we learn to read beauty, a path to freedom, not a marker of taste. For designers and art directors, it is a lifelong mission, to decode, elevate, and share beauty in its most diverse and democratic forms. It takes multiple shapes, lives in everyday gestures, and speaks the language of subcultures. But to access the emotion it offers, a sense of balance, of freedom, even a quiet joy, one must first learn how to read its codes.

—Beauty, like truth and justice, is a need of the people. The task of architecture and design is not only to create a better environment, but to offer beauty to everyone.

When Research Changes the Question

A few years ago, a renowned luxury school invited us to create a course on the aesthetics of luxury. We took on the challenge with curiosity, trying to shape a contemporary perspective on a subject as ancient as civilization itself. Quickly, however, we encountered a far broader issue: beauty is so vast, so elusive, that it resists easy definition. For a time, we hesitated to address it head-on, aware of its many intangible and contradictory forms.

As our research unfolded, we found ourselves in a universe of recycled images, tired narratives, and aesthetics drained of meaning, polish for polish’s sake. What began as a pedagogical brief became a deeper inquiry: why is beauty so often treated as the preserve of the elite?

Our vision gradually evolved. Beauty, we realized, is not surface, it is depth. It shifts with cultures, generations, even moods. It can arise from geometry or from asymmetry, from a single unexpected detail or a spontaneous gesture. It can be silent or spectacular. It resists universal rules.

—Beauty is not surface, it is depth. It resists universal rules, and shifts with cultures, generations, and gestures.

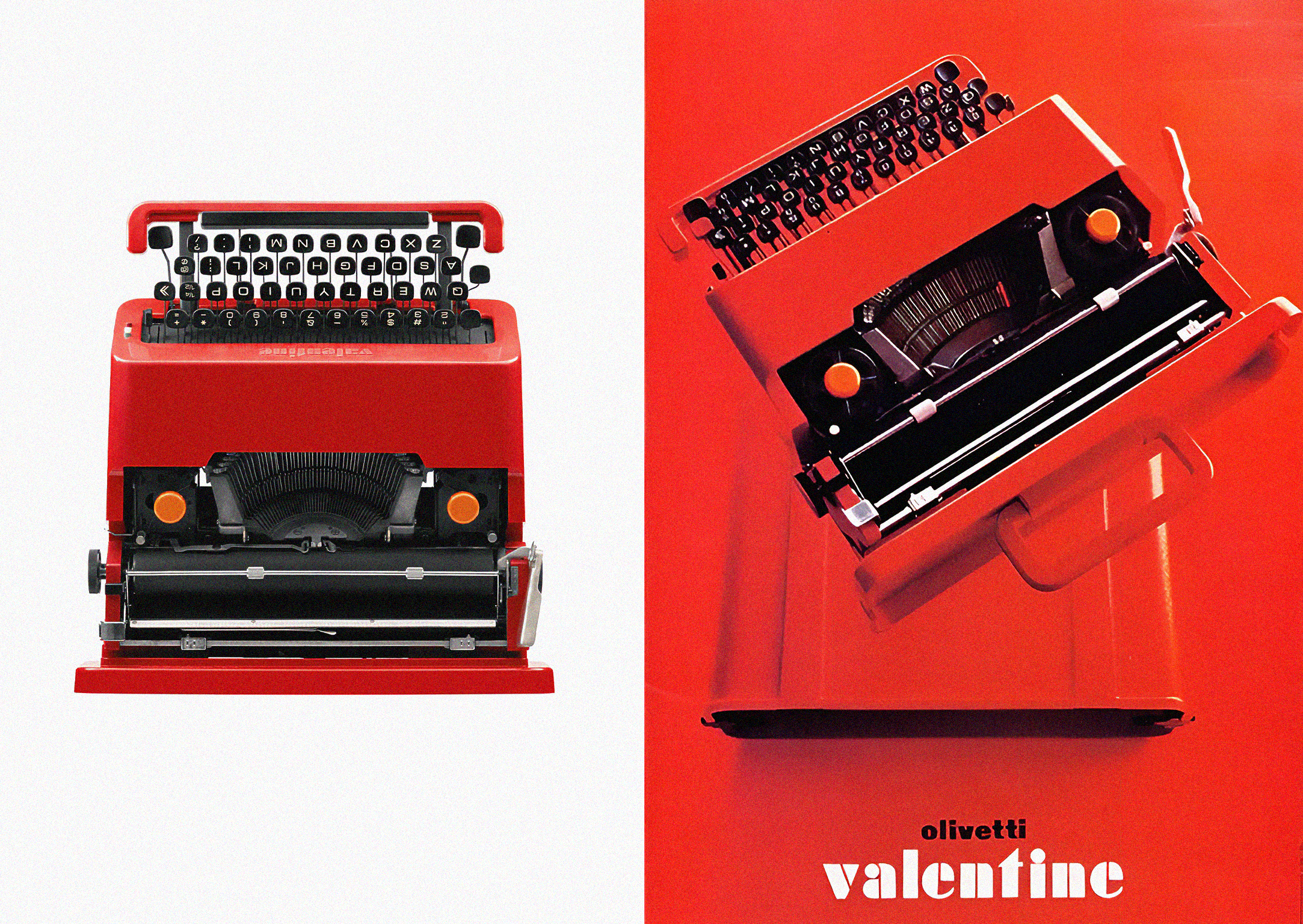

The course was never launched. But the reflection has never left us. What remains is a conviction: beauty should never be a privilege, and aesthetic codes should never act as barriers. Beauty must not belong only to those with means, networks, or pedigree. As Adriano Olivetti said as early as 1950, beauty, like truth and justice, is a human need. And it is the duty of architects and designers to make it accessible to all.

Like him, we believe beauty is a form of freedom, open to anyone who can access it. Aesthetics are the codes that open the door to that realm. They are not polish or sophistication, but a structure of meaning embedded in the rhythm of daily life. These codes vary not only across subcultures, but also from one civilization to another, shaped by geography, era, and worldview. Above all, they represent a context-aware language, never a superficial indulgence.

Understanding Beauty Versus Aesthetic

In common language, the two terms are often used interchangeably. But beauty and aesthetic are not the same.

Beauty is a perception, an effect, an emotion, an experience we feel. It is immediate, sometimes piercing. Aesthetic, on the other hand, is a framework of thought: a system of codes, references, and structures that either make beauty possible or seek to explain it.

—Beauty is a fact. Aesthetics is a reflection on that fact.

As philosopher Étienne Souriau noted, beauty imposes itself on us as experience, while aesthetics arises from analysis, from composition, from language. It is a way of thinking about what beauty provokes in objects, images, or sounds.

In the same spirit, art critic George Santayana described aesthetics as “the rational analysis of the emotion of beauty” (The Sense of Beauty, 1896).

In short: beauty is what we feel. Aesthetic is the system that allows us to feel it. One can have a strong aesthetic without triggering beauty. And beauty can emerge without any conscious aesthetic framework.

From Intention to Inclusion

This distinction matters. Our goal here is not to promote uniform taste or a universal style, but to advocate for access, to the cultural, emotional, and sensory tools that make beauty possible.

Aesthetic is often mistaken for something decorative, optional, or elitist. This misconception only deepens the sense of exclusion among those who feel beauty isn’t for them. But true beauty is neither frivolous nor exclusive. It shapes not only how things look, but how they feel, how they function, and how they connect us to others.

—Beauty belongs to no one, it is for those who pursue it. It can find a place in every life, every space, every gesture. But only if we learn to see it, recognize it, and give it the attention it deserves.

The idea that aesthetic is reserved for luxury persists, as if beauty were simply a marker of class. But that’s reductive and false. Philosopher Alain de Botton reminds us that the difference between a pleasant place and a hostile one often lies in the smallest details (The Architecture of Happiness, 2006). Beauty isn’t about cost, it’s about care. Not about luxury, but intention.

From Culture to Code: Navigating the Aesthetic Landscape

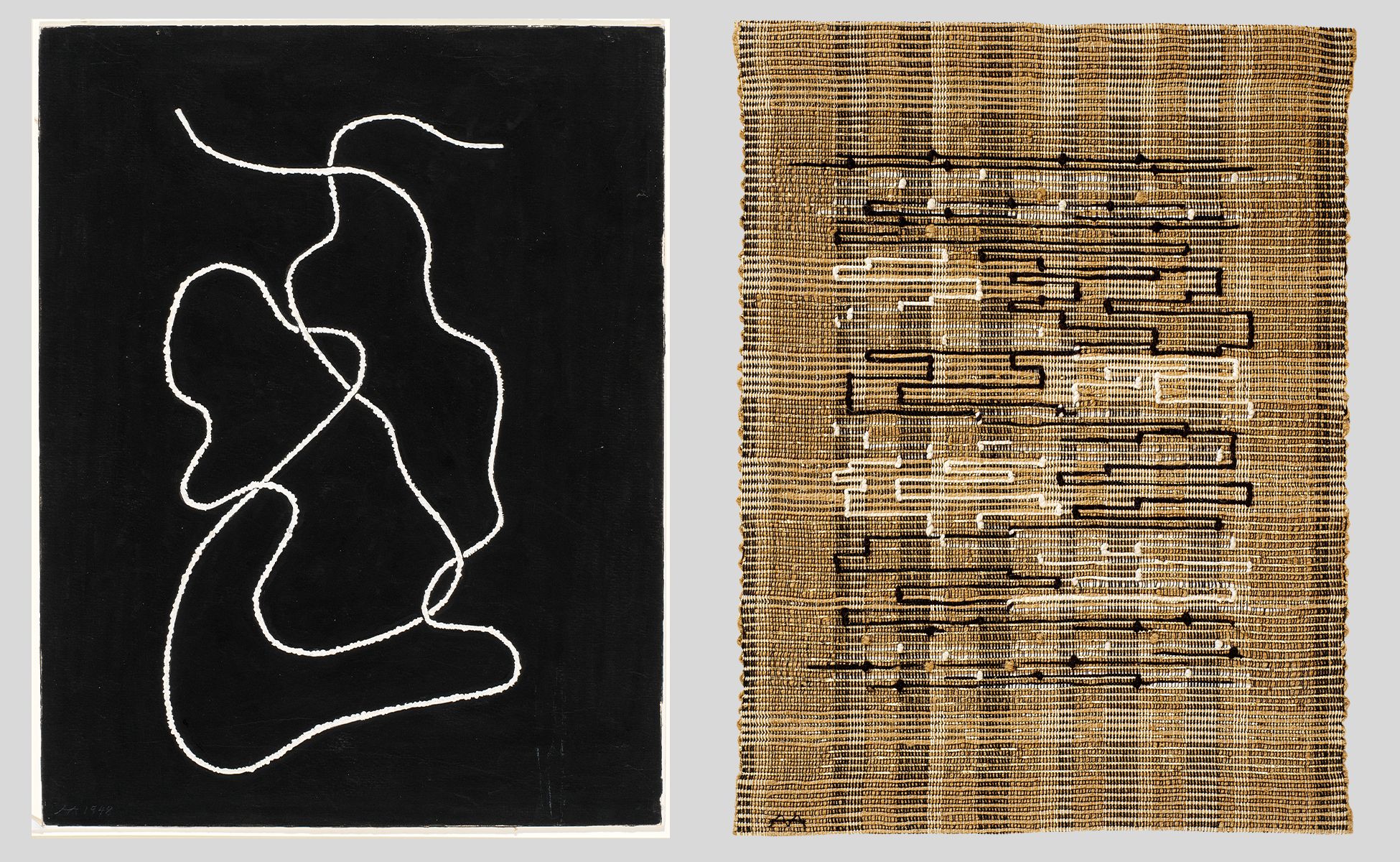

Our reflection has led us to believe that beauty that beauty is inseparable from culture. More precisely: from knowledge of a culture, and the ability to recognize its aesthetic codes. This recognition acts as a kind of literacy, a way of interpreting symbols, forms, and signs within specific social or visual contexts.

At the studio, we call them insights: interpretive keys, passports to subcultures, to borrow the sociological definition by Dick Hebdige (Subculture: The Meaning of Style, 1979), for whom a subculture is a form of expression and resistance, articulated through style.

Over the past twenty years, our work has taken us through a wide range of cultures and places. From the cinematic language of North Africa to the Japanese philosophies of Ikigai or Mingei; from the intricate world of watchmaking complication to the delicate art of casting international fashion models; from the closed codes of finance to the rituals of architecture, the arts, and the everyday experience of food. These are just a few of the subcultural landscapes we’ve explored, each with its own set of cultural and aesthetic codes, each asking for curiosity and a real desire to understand.

These codes can be learned. They can be trained. Freedom, like aesthetic sensibility, is something we cultivate.

Why Our Brains Trust Beauty

If beauty creates connection, it is because we are, quite literally, wired to respond to it. Neuroscience shows that aesthetic pleasure isn’t a superficial indulgence, but a deep-seated mechanism for orientation, reassurance, and trust.

This intuitive connection has ancient roots. Symmetry, in particular, has long shaped our perception of beauty. The word itself comes from the Greek symmetria, meaning harmonious proportion, a concept that dates back to 2000 BCE in Sumerian decorative logic, and was formalized by Polykleitos in classical sculpture. Through the Renaissance, it evolved in works like Divina Proportione by Luca Pacioli and De Corporibus Regularibus by Piero della Francesca. Kepler would later see in symmetry the “geometric order of the universe”, a divine structure, made visible.

This fascination with form didn’t stop at art or philosophy. It continued into science, in crystallography, in molecular biology, in the invisible geometry of physical laws. Thinkers like Hermann Weyl and Ettore Majorana showed how beauty and symmetry remain central to how we interpret the world. Symmetry still shapes how we experience space, image, and meaning, anchoring our sense of coherence in a complex world.

—Beauty will save the world.

Designing for Trust, Emotion, and Dignity

Why does beauty matter so deeply, neurologically, emotionally, socially?

According to Anjan Chatterjee (The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art, 2014.), our brains are drawn to symmetry, balance, and contrast, not out of vanity, but because these forms have historically signaled health, safety, and stability. Beauty becomes a guide, a sensory compass.

When we perceive something beautiful, we don’t just like it, we trust it. That trust affects how we interact with places, people, and messages. In cities, schools, hospitals, or communications, beauty becomes a deeply human tool, not to seduce, but to move. Abraham Maslow placed aesthetic needs high on his hierarchy of self-actualization. He saw that aesthetic wasn’t a luxury it was a condition for flourishing. In this light, beauty becomes care. It becomes responsibility.

Sometimes, when we speak about our work outside the design world, people ask: what is your profession, really? The answer is not always easy. In an age when AI claims to generate beauty, when contemporary art prioritizes concept over aesthetic, when function is left to algorithms, the fight for beauty feels more necessary than ever.

—Beauty becomes care. It becomes responsibility. It becomes a structure of empathy.

In our practice, design and art direction, we see beauty not as a final touch, but as structure. Not as perfection, but presence. Aesthetic is not polish. It is a mission to awaken beauty’s emotional power and make it shared.

The desire to make the world more beautiful, for everyone, is our motor. It gives meaning to our practice, and to our very existence.